The triple option play has been a staple in American football since the early 1900s.

For a play to be termed as an “option”, there must be an option for the quarterback to either hand the ball to his running back, or to keep the ball and run. The third phase is the pitch phase, where the quarterback can now choose to distribute the ball to a third option by pitch (traditional) or throw (modern).

The Option Advantage

The advantage of running an option scheme is to essentially block nine of the eleven defenders, use smaller and quicker linemen, and deceive the defense with many moving parts. The scheme became popular at the University of Texas, which originated the “wishbone” formation under head coach Darrell Royal, and eventually to Nebraska in the 1970s with a dominating era of football under Tom Osborne.

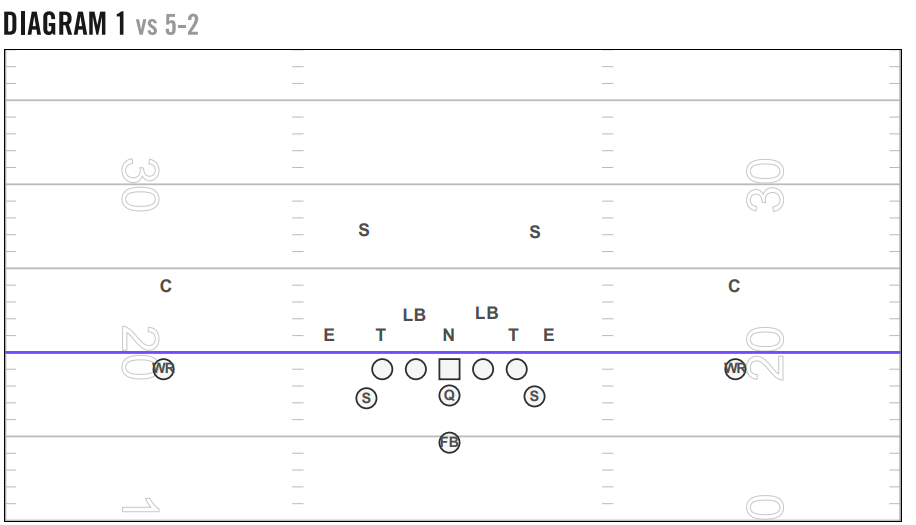

The wishbone transformed into a two-back formation, or “split back” with Bill Yeoman at the University of Houston. Split back veer ruled the football field until the 1980s, when the Naval Academy adopted the “Flexbone” under head coach George Welsh and offensive coordinator, Paul Johnson. Navy used an option scheme incorporating three running backs into the backfield but using quick pre-snap motion to gain an advantage at the attack point. Paul Johnson also used a spread formation that placed his receivers near the numbers, spreading the defense out across the entire field (diagram 1).

Johnson’s influence in the option scheme spread throughout the country after his tenure with Navy, Georgia Southern, and Georgia Tech. Defenses had to adjust to his unbalanced, trips, and tackle-over formations while staying disciplined in taking away the three phases of the triple option.

Beyond stopping the run game, defenses had to account for Johnson’s play-action, screen, and rollout pass game. The result was a 127-89 head coaching record in Division I, along with back-to-back national championships and a 62-10 record at Division I-FCS Georgia Southern. His offense influenced every level of football, from high school flexbone to college zone read, to NFL spread options.

Triple Option Breakdown

Let’s take an in-depth look at the three phases of the triple option.

Specifically, we will cover inside veer. A typical option offense will only be as successful as the splits between their offensive linemen. Although this can vary, three-foot splits are ideal for the dive phase. The dive back (usually the fullback) will reach the line of scrimmage in less than one second. The dive read is always identified as the first-person head up to outside of the play side tackle (#1).

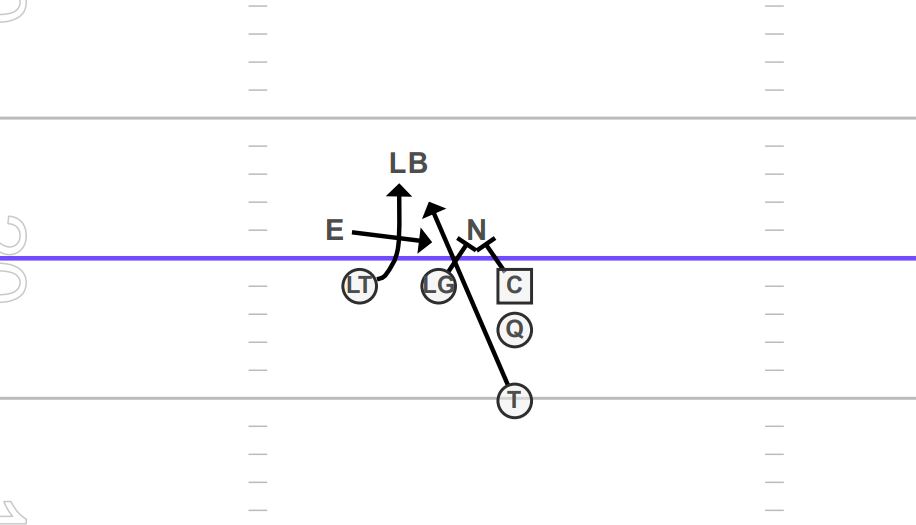

In diagram 2, you can see that this defender (a 5 technique) is roughly 7 feet away from the path of the fullback, or the inside leg of the guard. Moving 7 feet in less than a second is fast. And it must be pre-determined before the snap. In theory, a defensive end outside of the tackle should never be able to take away the dive on inside veer, or any option play attacking the A/B gap.

A popular phrase for the quarterback’s option mechanics is “ride and decide.”

When the quarterback takes the snap and puts his toes on the path of the dive, he extends the ball into the belly of the dive back, creating the “mesh.” He will then have less than a second to determine if he will give or keep the ball. When the defender aggressively slants to the dive, the QB will pull the ball from the mesh and execute the next phase.

Depending on the offense’s scheme and philosophy, the QB will either attack #2 (first defender outside of #1) or keep a tight running path replacing the heels of #1 (diagram 3). If the second read is responsible for taking away the QB’s run, then it is time to execute the pitch phase. This can be done in the shotgun as well, often making the decision time much slower, but allowing the QB to have a better vision of his read.

In the flexbone, the pitch back is already in motion at the snap. Paul Johnson used the phrase “late and fast” to describe the timing of the pitch back’s motion.

Usually, he is sent by a foot tap of the QB, or from the cadence. Once the ball is snapped, the pitch back needs to be roughly 4 yards away from the QB to put #2 in conflict. Once #2 begins to tackle the QB, he will pitch the ball to his pitch player running north (diagram 4).

This is when you will usually get an explosive play since the safety is most likely filling for the QB or attempting to tackle the dive player if his eyes are undisciplined. In some cases, the QB will evade #2 and continue the pitch phase to the safety, which can be risky but provide a high reward if the ball is pitched at the third level.

Adding the Pass to the Triple Option

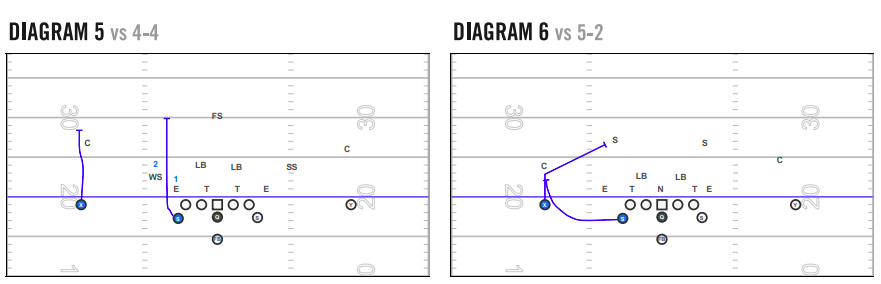

Now, about the pass. There are two basic blocking schemes on the perimeter, man, and switch. In the man scheme, the WR will stalk the cornerback with the play side slot stalking to the alley player (diagram 5). In a switch blocking scheme, the WR will push vertical for three steps and then crack the alley defender, while the play side slot will arc release to the cornerback (diagram 6).

If either of these defenders are causing havoc in the run game, they can be exploited in the pass game. Two of the most common pass concepts to deal with these conflicts are vertical and switch (post/wheel) route combos off veer play action. In diagram 7, you see the alley defender is the conflict for the run game.

The solution is running a 3-man vertical route with backside motion anticipating a touchdown thrown over the safety’s head. In diagram 8, you can see the cornerback is playing with his eyes in the backfield and adding a hat to the defense’s advantage.

While the vertical concept would still attack him, a switch concept would result is theoretically throwing the ball over the cornerback’s head to the slot on his wheel route. Both combinations can be explosive against an aggressive “stop the run” defense.

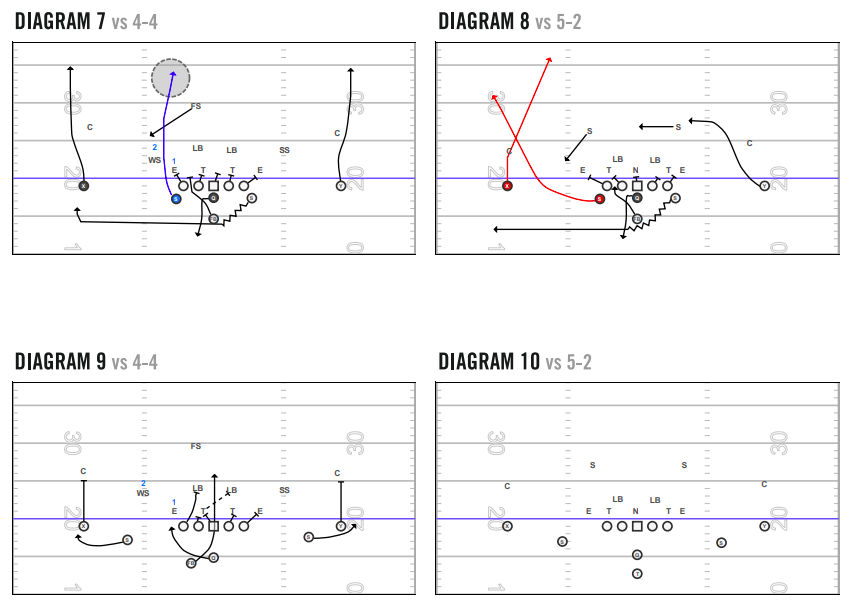

As with most “spread” offenses in the shotgun, the use of bubble screens can happen both pre-snap and post-snap. Originally, the bubble screen replaced the pitch phase on the zone read play by putting #2 in conflict (diagram 9).

The QB can still ride and decide, but now he has the option to throw the bubble, thus, the evolution of the run-pass-option (RPO). The bubble screen was also used as a pre-snap outlet for the QB if he didn’t like the numbers in the box.

This “access” throw allowed him to catch the snap and throw the bubble immediately based on his perimeter defenders’ alignment. Either way, whether gap scheme or zone, there are many option offenses to this day at each level.

The first version of the modernized flexbone is the pistol alignment (diagram 10). It is the same flex formation, but the QB is in the shotgun with the slot backs in receiver positions. The same option plays can all be executed, but now the timing will be slower, and the QB’s reads will slow down.

Rich Rodriguez implemented an option scheme at West Virginia with Pat White and Steve Slaton, going 33-5 in three seasons. As Paul Johnson moved on from Georgia Southern, his option scheme lived on, transitioning to a split back inside zone scheme (diagram 11).

The most popular option offense in recent years in the post-Johnson college football era is Coastal Carolina. Coastal’s historic season in 2020 proved that a spread-option offense can be successful while still implementing gap schemes for the offensive line. Diagram 12 shows three plays from their base scheme. The Coastal staff (now at Liberty) has roots in flexbone and triple option football that they implemented into a spread pistol offense that fits their personnel.

QB Grayson McCall was the perfect fit to run the offense, having an option background at his North Carolina high school program. One of Coastal’s top plays was the counter speed option. This is a shotgun variation of the traditional flexbone counter option, but provided a quick, downhill perimeter run to catch a defense off guard (diagram 13).

Zone or Gap Scheme

Now the question is “zone or gap scheme?”

The answer is in your personnel.

In the flexbone option offense, the dive back was usually a downhill runner that would punish defenders in his running lanes. For spread offenses with shifty running backs, the dive back can weave his way through the zone blocking, allowing him to find running lanes both play side and backside. The blocking scheme is essentially the same, except for the backside.

The solution for gap scheme offenses is to have cutback and counter schemes built in for answers to backside defenders being over aggressive. Division II National Champions Ferris State run a triple option scheme from the shotgun. They use GT counter as their base scheme, along with midline triple from a 2×2 spread formation (diagram 14). The results: 115-17 record with 2 national championships since 2012.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the triple option is a classic concept that still puts a defense in conflict.

Typically, a defense will have less than 4 days to create assignments and practice them correctly to stop an option attack. When determining which option schemes you can implement, your decision should always be made knowing your personnel, specifically your quarterback.

If he is a pure runner and your best athlete, you’ll want him with the ball in his hands while blocking only nine defenders. If he is a passer, you should consider the RPO scheme to allow him to attack gaps in the defense pre- and post-snap. When a defense is stuffing the run game, it’s time to attack them through the air, or to always keep them honest. If you can establish the run, you will create opportunities for your pass game to generate explosive plays.

Ultimately, blocking nine defenders and finding the best scheme to fit your players will give them the best chance to be successful, and the option provides a great opportunity to do so.